Changing Colours: The Original and the Replica

The displayed Nydam Boat, a rowing boat from the 4th century A.D., is considered an archaeological highlight, which is exhibited in the Archaeological Museum Schloss Gottorf in Schleswig. While the find was excavated in Denmark in 1863, it has been located in Germany since the 19th century. For a long time the question of ownership was controversial, but today the boat symbolizes a cross-border understanding of history.

In the exhibition, the boat attracts attention by its size and appearance – it looks 'old' and is obviously the 'real thing'. However, the exhibited boat differs from the historical original: After its salvage, the boat was reconstructed from single parts – and later also remodelled. In the process, components that were not available as excavated finds were also added. Further, the dark colour of the wood is striking. Because of it, the boat seems old.

However, the boat probably looked different in the past: Not only in form, but also in colouring, because wood changes its colour and appearance through time. It is also possible that the boat was painted. The past might have been colourful, but most of the colours are gone today – what remains are colourless stone and dark wood.

In 2013, a replica of the Nydam Boat was built near the excavation site. Today, the ‘Nydam Tveir‘ is used as a rowing boat. The replica resembles the original in many aspects. However, the colour of the wood is striking: The boat on the photo is lighter – 'honey-coloured'. It seems new.

The light colouring contradicts what is known from museums, where old wooden objects are often dark. Today the replica is already darkened and not as bright as it was when it was built. However, as wood changes due to water and weathering, the present colour of the replica is perhaps closer to the historical original than the archaeological find and the exhibit in the museum would suggest?

The Nydam Boat in the current exhibition in Schleswig | © Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf, Landesmuseen Schleswig-Holstein. | Location: Castle Gottorf, Schleswig-Holstein.

‚Nydam Tveir’ | © E. Christensen, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 3.0. | Location: Alssund near Øster Sottrup, Denmark.

More than just a Fountain: Water Stress on Tenerife

For many of us, the image here is just a picture of a fountain. Where water supplies are taken for granted, such an image may stir up mental images of children playing gleefully with water in a public space or maybe of a dog seeking refreshment on a warm summer day. But for many early modern island residents, the sight of the above fountain from Icod de los Vinos in Tenerife would trigger other associations, such as contentious questions over the proper allocation of limited hydraulic resources. Who should receive water first when water resources are scarce? Farmers Hospitals? Foreign vineyard owners who could pay the highest price? Was water a common good to be distributed equally or a commodity for sale? Who decided this, and how?

Water scarcity affects many islanders, due to slightly salted (brackish) groundwater in addition to few or a lack of permanently flowing rivers. Volcanic eruptions often exasperate these concerns by polluting aboveground freshwater with volcanic ash and belowground aquifers with toxic volcanic gasses. The problem of limited hydraulic resources on islands reaches back in time for thousands of years and continues into the present.

Today it is no coincidence that Tenerife, Malta, and Cyprus score highest on the water exploitation index (WEI) of the European Union. Accordingly, the interdisciplinary work group “Insularities / Insularitäten” of SFB 1070 ResourceCultures, researches water stress on islands. Historians and archaeologists analyze documents and material culture to better understand cultural goods like the above-depicted fountain. In line with the SFB 1070 understanding of resources, it can be shown that decisions regulating the distribution of limited resources were influenced by geology and geography, as well as by demographic factors, social structures, legal regulations and religious beliefs (see for example: Bartelheim/Montero Ruíz 2009; Teuber/Schweizer 2020; Dierksmeier 2020).

Fountain from Icod de los Vinos | © L. Dierksmeier | Location: Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain.

Composition of Power

In 2002, a rosette made of gold, carnelian and lapis lazuli was found in the Royal Tomb of Qaṭna. It is a prime example of how Syrian artisans were able to combine precious materials more than 3000 years ago. The resulting objects were symbols of prestige, as they conveyed a clear message of beauty, power and wealth. In the case of the rosette from Qaṭna, it was not only the aesthetic value of its sequence of blue (lapis lazuli), red (carnelian) and yellow (gold) colours but also the implications linked to the materials in use, which added to its overall symbolic value. Because gold, carnelian and lapis lazuli were not naturally present in Western Syrian, the rosette emphasized the political as well as economic potency of its owner: Lapis lazuli, for example, had to be imported from Afghanistan, over thousands of kilometres.

Rosette | © P. Frankenstein a. H. Zwietasch, Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart | Finding location: Qaṭna (Syria), Royal Tomb | Location today: National Museum of Damascus

The tiny gold hangers on the back of the rosette had been inserted at regular intervals into the slightly recessed lamellae. They show that this piece of jewellery was originally attached to a base of fabric or leather, perhaps a dress, a belt or a headband, which has not been preserved. The piece was found between several human bones and pearls. In this respect, the rosette may have once served as a prestigious burial object in the Royal Tomb under the palace of Qaṭna.

The rosette is made of gold, carnelian and lapis lazuli and has a diameter of approx. 6,6 cm.

Back of the rosette | © P. Frankenstein a. H. Zwietasch, Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart | Finding location: Qaṭna (Syria), Royal Tomb | Location today: National Museum of Damascus

The Story beneath our Feet

The soil tells a story. In this profile, the soil horizons can easily be distinguished by colour. The dark brown stripe with the embedded river gravel at 1 to 1.2 metres below the present surface catches the eye. This humus-rich horizon shows the former land surface at this location. Younger soil material has been deposited above it, with further observable colour changes.

The first soil horizon directly above the old land surface dates back to the Bronze Age. Due to continuous soil cultivation in this area during that time, soil erosion occurred on the upper slope and led to the burying of the former land surface. This was followed by a stable phase, during which another horizon rich in humus was formed, which was the land surface for a while. A further erosion phase followed and the surface was covered again. The soil profile, thus, documents the intensive agricultural use from the Bronze Age to today and shows that people change the landscape considerably through time.

Soil profile of a colluvial deposit, which shows a former land surface | © S. Teuber | Location: Wilflingen-Hirschlen, Southwest Germany

Mercury: Deadly Toxin or Effective Medicine?

With a metal content of 87 %, cinnabar is the most important mercury mineral and is used in South Indian medical traditions, such as Siddha medicine, to cure skin diseases. In Siddha medicine different minerals play a role besides medicinal plants, but cinnabar is of special therapeutic importance. In South India the mineral is called “lingam”, which is also the name of the phallic representation of the Hindu god Shiva. After all, liquid, elemental mercury is considered as the seminal fluid of Shiva and as a material of special (healing) power. Traditional doctors in South India extract liquid mercury from cinnabar. The substance is then thoroughly cleaned, processed and used as an ingredient in medicines. Such mercurial medicines are used, for example, as emergency medicine for snake bites and even as therapy against cancer.

Cinnabar was widely used as the pigment ‘vermilion’ from ancient times until the 20th century. In Germany, the use of the mineral and other mercury-containing substances is now strictly regulated, not least since industrial accidents have led to severe effects on humans and the environment. In Japan, for example, the so-called Minamata disease occurred in the mid-1950s after the chemical company Chisso had discharged mercury compounds into Minamata Bay, which contaminated fish, drinking water and, finally, the human population.

Cinnabar or mercury sulphide (HgS) being ground in a mortar | © R. Sieler | Location: Tamil Nadu, Indien

Jewel in Miniature Format

The gemstone found in the Royal Tomb of Qaṭna impressively illustrates the connection of different cultures. The shape of its upper side was modelled after a scarab, a tradition that spread from Egypt to the Orient. The seal image on the flat underside shows a woman wrapped in an ankle-length cloak with a headscarf. Her posture and clothing do not correspond to an Egyptian, but to a purely Old Syrian sense of forms. This is remarkable, as the design of the woman suggests that the seal was produced at a time when the Royal Tomb was at the start of being built. The striking purple stone, set in gold, could therefore be an heirloom of the royal family of Qaṭna. If one considers that the seal image depicted is hardly longer than 2 cm and not wider than 1 cm, the artistry of the Old Syrian craftsmen becomes evident.

Scarab | © P. Frankenstein u. H. Zwietasch, Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart | Finding location: Qaṭna (Syria), Royal Tomb | Location today: National Museum of Damascus

Chosen by the Gods: The King and his Power

In Ancient Near East, most kings describe themselves as having been chosen by the gods to rule. The Arsuz stele provides us with an iconographic depiction of this relationship between the king and the god. Found on the coast of Turkey, the stele, dated to the 10th century B.C., shows a deity and a king standing on a bull, the symbol of the god. Under a winged sun disc, emblem of divinity and royalty, the ruler holds a bunch of grapes with his right hand, and an ear of wheat with his left hand. In front of him, the Storm-God holds in his left hand a trident-shaped thunderbolt while he holds the wrist of the ruler with his right hand. The inscription accompanying the relief tell us that the stele was erected by king Suppiluliuma after a successful military campaign. In the text, the ruler expresses how he was supported by the gods, especially by the Storm-God, at the head of the divine hierarchy, who “put his hand” on him, thus ensuring his victories in battle. The ruler needed also the favor of the Grain and Wine deities, depicted as the attributes of the king, who offer him prosperity to his reign. The relief, which shows that the power of the ruler and his success in life was believed to depend on his selection by the gods, became a resource in the legitimation of the royal figure and in the enhancement of his authority.

Arzuz Stele in Antakya Archaeology Museum, Turkey | © G. Paradiso

Stone Doughnuts of Iran

These doughnut shaped stones were found in shrines in Iran. They generally measure between 5 and 15 cm in diameter, but can be bigger than 20 cm in diameter. All stones have a rounded shape. Most of them are pierced in the middle and, thus, resemble the modern day doughnut pastries. The doughnut stones differ in color but are mainly light colored.

During the visit of one shrine, we met a man who was engaged in the drilling of a stone, creating the typical shape. He told us about the religious function these stones have today: “with each stone we commemorate a dead person”. However, not all doughnut stones are new. During our research we discovered this type of stone in ancient sites dating back to the Early Bronze Age (ca. 4600-4500 years ago). Local people use these ancient sites to collect the stones in order to place them in the shrines.

Site A3 - Moshā Dād Abbas | © M. Karami

The doughnut stones are placed in roofed and roofless shrines, which are located close to the Islamic cemeteries. Normally, both types of shrines are small. All roofed shrines have a circular form while the roofless ones are usually constructed oval. The floor of the shrines is frequently covered with carpet and it is not allowed to enter a shrine while wearing shoes. Within the shrines platforms exist on which the stones are placed.

Due to the collection and production of the stones in present-day Iran, it can be difficult to determine how old the stones found in the shrines are. However, the stones of Site A24-Golnābād and Site G21-Tom-e Dehno Mohammad Rezā Khān II were discovered alongside Early Bronze Age pottery and chlorite vessel pieces. While we know the function of the stones today, it remains a mistery how and why these types of stones were produced and used in ancient times.

Site A24-Golnābād or Kohan | © R. Zarifian Yeganeh

Warriors and Cats

Although the domestic cat, as one of the last classical domestic animals, did not reach Scandinavia until some centuries after Christ’s birth, the velvet paw originating from the Near East was already omnipresent in the Viking Age between 800 and 1100 AD. Their role in Viking society has hardly been studied so far, and is often associated with cult and magic, influenced by later literary, mythological sources. Thus, according to the Norse mythology, the car of the goddess of love Freya is pulled by two cats and in the sagas cats appear as companions of seers and witches. However, the increasing number of new archaeological finds of cat-bones hints at a completely different image of the cat familiar to us modern humans; as a useful pest controller and highly esteemed pet that was given to women, children and sometimes even warriors to the grave, probably as a beloved playmate and companion in the afterlife.

Cat in front of Viking weapons | © M. Toplak, Universität Tübingen

A Pig got lucky

Fortunately, the DFG SUV arrived at the right time for the Ibérico pig in the Dehesa. These curious animals are a native breed that is associated with the southern Spanish Dehesa landscape in the regions of Extremadura and Andalusia like no other animal. Only the Dehesa allows a species-appropriate, that is extensive and semi-wild attitude of the pigs. The Ibérico pigs genetically close to the wild boar exploit an unprecedented amount of acorns (bellotas) of the stone and cork oaks that are typical of this landscape. Cleverly they crack their shell and eat at least 500 kilograms per snout during the montanera, the two-month acorn mast before they are slaughtered. When half of the carcass weight of pigs is harvested by the acorns and grass during the montanera, it gives the famous jamón ibérico de bellota its characteristic nutty flavor.

Amphorae from Egypt

Depicted are two amphorae made of alabaster, a soft, light-coloured stone, which is visually attractive due to its natural banding. The vessels were found in the Royal Tomb of the ancient Syrian city of Qaṭna. They date back to the 2nd millennium B.C.E. One of the handles of the larger amphora has only survived partially. While the right vessel was made of one piece of stone, the left vessel’s base and body are separate components.

The shape and construction of the two vessels are influenced by Egyptian models, which were very popular in the Western Syrian and Levantine areas of the Late Bronze Age (ca. 1550-1200 B.C.E.). Vessels like this were imported from Egypt, but also produced locally. In this respect, the presentation of such containers by royalty suggested the ability of a Syrian ruler to obtain exotic items from faraway countries. Furthermore, they indicate the power, which the ruler must have had over the production and distribution of such objects.

Two Amphorea | © P. Frankenstein and H. Zwietasch, Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart | Find location: Qaṭna (Syria), Royal Tomb | Location today: Homs Museum

Sometimes it takes Luck – Digging Work in Grüningen

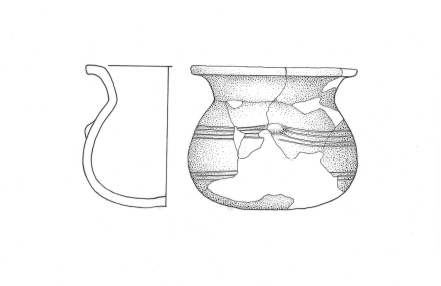

Archeology is often favored by chance. During a soil profiling near a Bronze Age settlement, the excavator suddenly found a ceramic vessel. The subsequent exposure by the archaeologists Prof. Dr. Thomas Knopf and Dr. J. Miera Ahlrichs showed that two presumably placed vessels (see illustrations / photo) had been deposited at this exact location. The condition of the vessels suggests that they were deliberately deposited in this location. The vessels come from the so-called ‘urnfield time’ (1200 – 800 BC), which is dated to the end of the Bronze Age (2200 – 800 BC). Such landfills are usually associated with ritual acts, such as sacrifices. It would be conceivable, for example, that formerly organic substances (for example foods or liquids) were deposited in the vessels which could not be preserved in the mineral soil.

Vessel from the urn field period | © H. Jensen, Institut für Ur- und Frühgeschichte und Archäologie des Mittelalters

Drawing of the vessel | © M. Möck, Institut für Ur- und Frühgeschichte und Archäologie des Mittelalters

Water Scarcity in the Sea

This underground cistern with a size of 12 to 90 m³ was dug on Linosa in the upcoming rock of the mountains. The mountain slopes were smoothed to serve as a rainwater catchment area collected in the rainier months between autumn and spring. On the island of Linosa, just 5.2 km², one of the Pelagie Islands in the Strait of Sicily, between the southern Italian and North African coasts, more than 100 cisterns were built in antiquity. As on many other Mediterranean islands, the supply of drinking and service water on Linosa is a permanent problem due to the scarcity or lack of natural freshwater sources.

The island of Linosa was uninhabited since late antiquity until the 19th century and was re-populated in 1845 by the Bourbon kingdom of both Sicily. The first generations of settlers used the ancient cisterns more than 1000 years old to provide water to the newly established colony.

Catchment and cistern for collecting and storing rainwater on the Mediterranean island of Linosa | © Frerich Schön

The Monk in the Pond

As monk one calls a symmetrical construction that controls a cavity through pipelines in the bottom of the pond and the water level in these dust collectors. So you can desludge or fish off the pond. You can find these constructions since the Middle Ages. The unusual name indicates the historical development of the pond economy. In the Middle Ages it was above all the monasteries - and thus the monks - who created and cultivated the ponds, because fish farming was important due to the strictly regulated meat consumption. Ponds thus shaped the medieval landscape. However, they not only served the fish farming, but the sludge was used as fertilizer. In smaller ponds flax could be roasted, tiller stored or ice for cooling in summer. The monk in the pond is therefore a cultural and historical phenomenon that shows the close connection between pond management and the monastery world.