The Vikings

The 'Viking'

Assassin’s Creed:

Valhalla

The Vikings: A Myth between Pop Culture and Culture of Remembrance

The Vikings are omnipresent in pop culture. Most people will recognize a Viking – for example by a horned helmet – or will be able to identify a Viking ship: The long and narrow shape, the shields on the railing, rudders as well as sails, often with red and white stripes, and the dragon's head attached to the front of the ship (on the stem) – these are the typical attributes. These pictures often illustrate the idea of explorers, plunderers and conquerors who ravaged the world on their warships. These portrayals, however, tell more about our view of history than about historical realities. But where do these stereotypes come from and how authentic are they? This is what this exhibition is about, presenting the Viking myth as a brand, as a place of longing and as a source of identity.

Gokstad ship

Playground

PLAYMOBIL-Viking ship

Gokstad ship

The 'Gokstad ship' was excavated in 1880 near Gokstad in Norway. It was part of an elaborately arranged burial of the 9th century CE. The wooden ship is approx. 23.5 m long and could be rowed and sailed.

For a long time the 'Gokstad ship' was considered a typical Viking ship. However, no evidence of Dragonheads was found on the stems. Today, diverse ship finds illustrate a more diverse picture of the Viking Age: There were not only warships, but also merchant ships and smaller coastal ships, which were probably used for transportation and fishing.

The so-called Gokstad ship in the ‘Vikingskipshuset’ in Oslo. | © Museum of Cultural History, University of Oslo, Norway. Photographer: Unknown. Lizenz: CC BY-SA 4.0

Object details:

Object: Gokstad ship

Find location: Gokstad, Norway

Location today: Oslo, Norway

Material: Wood

Dating to 900 CE

The 'Viking'

The 'Viking', a replica of the 'Gokstad ship', was built in Norway in 1891. The crew crossed the Atlantic with the 'Viking' to prove that Viking ships were seaworthy and to present Norway at the World Fair in Chicago.

At first glance, the replica looks like the original, but there are several differences: the stem is decorated with a dragonhead, a tent is set up on deck, and a foresail was installed (not displayed in the picture). Archaeologically, these attributes have not been proven– but does this make the replica less authentic?

The replica itself was the model for later portrayals, for example in the encyclopaedia 'Nouveau Larousse illustré' of 1898 and in the comic 'Asterix and the Normans' of 1967. Both portrayals of Viking ships have similarities with the 'Viking': they have a striped sail, shields on the railing and an animal head on the stem. They also have a tent on deck and a fore sail. Today there are many other ship replicas based on Viking Age finds, which are sometimes used for experimental purposes, for example to understand sailing characteristics.

The 'Viking', replica of the Gokstad ship, at the Chicago World’s Fair 1893.

Object details:

Object: The 'Viking'

Material: Wood

Dating to 1891 CE

PLAYMOBIL-Viking ship

Historical stereotypes are long-lasting. PLAYMOBIL produced a Viking dragon ship in 2002 and the current collection includes Vikings and a Viking ship: The toy ship is made of synthetic material, but design and colour of the ship recreate a wooden look. Obviously the 'Viking' and the 'Gokstad ship' served as models.

The decorated stems are striking: dragonhead and tail give the impression of a 'dragon ship'. Shields are attached to the railing; the sail is red-white striped – frequently used attributes in the portrayal of Viking ships. On deck of ship there are men and a woman who can be identified as ‘Vikings’. One of the figures wears a horned helmet, another symbol for Vikings. However, no archaeological evidence of horned helmets exists.

A 'Viking ship' by PLAYMOBIL from the current collection (status 2020) | © PLAYMOBIL/geobra Brandstätter Stiftung & Co. KG.

Object details:

Object: PLAYMOBIL-Viking ship (Article 9891)

Material: Synthetic material

Dating to 2020 CE

'Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla'

In digital media, the Viking Age is a popular setting for story telling. One of the latest digital games is 'Assassin's Creed: Valhalla' by Ubisoft.

Screenshots and trailers give a first impression of the Viking world portrayed here: It is a rough world where war prevails and where adventures can be experienced. The appearance of the Vikings suggests similarities to current TV series and differs from older portrayals of Vikings (such as Playmobil).

The ships, however, contain the familiar symbols – such as dragonhead and indicated tail. In addition, details such as colourfully painted boats, sails with motifs and carvings are also presented to create a denser atmosphere.

'Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla' – Ubisoft advertises to become a legendary viking warrior. | © 2020 Ubisoft Entertainment. All Rights Reserved. Assassin’s Creed, Ubisoft, and the Ubisoft logo are registered or unregistered trademarks of Ubisoft Entertainment in the US and/or other countries.

Object details:

Object: PC game cover of 'Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla'

Material: Digital illustration

Dating to 2020 CE

Playground

In contrast to opulent and detailed Viking games, the reduction to typical attributes is characteristically for this wooden Viking ship climbing frame on a playground in Schleswig.

The construction behind the mast is interesting: it resembles the burial chamber found on the 'Gokstad ship'.

It is no coincidence that the ship is located in Schleswig: The city markets itself as a 'Viking city'. Historically, it was not a Viking town, but rather the medieval successor settlement of the Viking Age site at Haithabu, which was located on the other side of the Schlei opposite Schleswig. Today, Vikings were and are a source of identity for the city of Schleswig, recognizable in the cityscape and also in marketing, where direct and indirect references to the Vikings are made.

A Viking ship in front of the Schleswig Cathedral – A climbing frame on a playground. | © T. Schade.

Object details:

Object: A Viking ship in front of the Schleswig Cathedral – A climbing frame on a playground

Location: Schleswig, Germany

Material: Wood

Dating unknown. Photo taken in 2020 CE

Moving Materials?

Obsidian

Marble

Moving Materials?

Trade has connected distant regions throughout human history. It is hardly ever a simple exchange of material goods (raw materials, food, tools), but also involves the transfer of knowledge, practices and technologies (intangible resources). By looking at objects, archaeologists, geographers and anthropologists can understand the complexity of these exchange relationships. Thus, the following objects from the fields of economy, culture and food show the influence of trade on the development of social structures – and how the mobility of goods and people can be traced through time.

Teeth

Cast Copper Cake

Tractors

Obsidian

These obsidian blades were found in a small village at the Tigris in northern Iraq. Obsidian is a rare volcanic glass formed by rapid cooling of lava. The discovered obsidian blades probably originate from geologically young volcanic regions of Anatolia. Through an ingenious technique, prehistoric man already used obsidian in a variety of tools such as weapon tips, knives and other cutting tools, but also in luxury items. Before the invention of metal, obsidian was the most important material for the production of weapons and tools.

Due to its glassy-glossy surface, obsidian is easy to identify and is used as a source of information for the reconstruction of prehistoric long-distance trade routes. In the laboratory, obsidian can be analyzed in order to determine the geographical origin of the raw material. As early as the Paleolithic and the Neolithic, trade networks extended from Europe to Asia.

Obsidianblades of Northern Irak | © S. Zarifian, EHAS Project

Object details:

Object: Obsidianblades

Material: Obsidian

Dating to 5000 BCE

Cast Copper Cake

During the Bronze Age (2nd century BCE), cast copper cakes were a valuable trading object and reached Anselfingen in the Hegau region, about 20 km west of Lake Constance. The Anselfinger cast copper cake probably came from the Alps, more precisely from the Eastern Alps. In order to process copper into a bronze alloy, tin had to be obtained from even greater distances, for example from Cornwall in England. Nevertheless, the expensive material was not only used for the production of luxury goods such as jewellery, but also to make everyday tools such as axes or sickles, which allowed more efficient woodworking and harvesting. The growing demand for bronze, but also for other products such as amber and salt, allowed long-distance trade beyond the region to flourish during the Bronze Age. Thus, the settlements of that time were often located near lakes and rivers, as these easily accessible areas were favourable for trade.

Bronze Age cast copper cake fragment | © J. Hald, Kreisarchäologie Konstanz

Object details:

Object: Bronze Age cast copper cake fragment

Find location: 2016 in Anselfingen (district of Constance) during a rescue excavation by the State Office for Monument Preservation and the District Archaeology Constance

Weight: The cast copper cake fragment weighs almost 2 kg and originally belonged to a piece weighing around 6 kg

Material: Copper, probably from the Eastern Alps

Dimensions: 20, 3 x 10,3 x max. 2,5 cm

Dating to 1500 BCE

Marble

The Corinthian capital of expensive Carrara marble originates from the Roman Aeclanum, a small provincial town in southern Italy. It is a special find for the rural region. Traditionally, buildings in Italy were wood-clay constructions. Through close contacts and trade relations with Greece, more and more stone buildings can be found from the late 2nd century BCE onwards. However, this capital does not consist of the local limestone. Instead, precious marble was imported from the Tuscan quarries near Carrara. This was an immense effort, because the marble had to be transported to this remote area via roads. The effort and cost of erecting a marble building underline the high idealistic value that the local population attached to the building. It is possible that the building was erected as an imperial cult building in honour of the new Emperor Augustus.

Corinthian capital in Carrara marble, Augustan, | © Christiane Nowak

Object details:

Object: Corinthian capital in Carrara marble

Find location: Aeclanum, southern Italy

Location today: Avellino, Soprintendenza

Material: Marble

Dating to 10 BCE – 10 CE, Augustan

Teeth

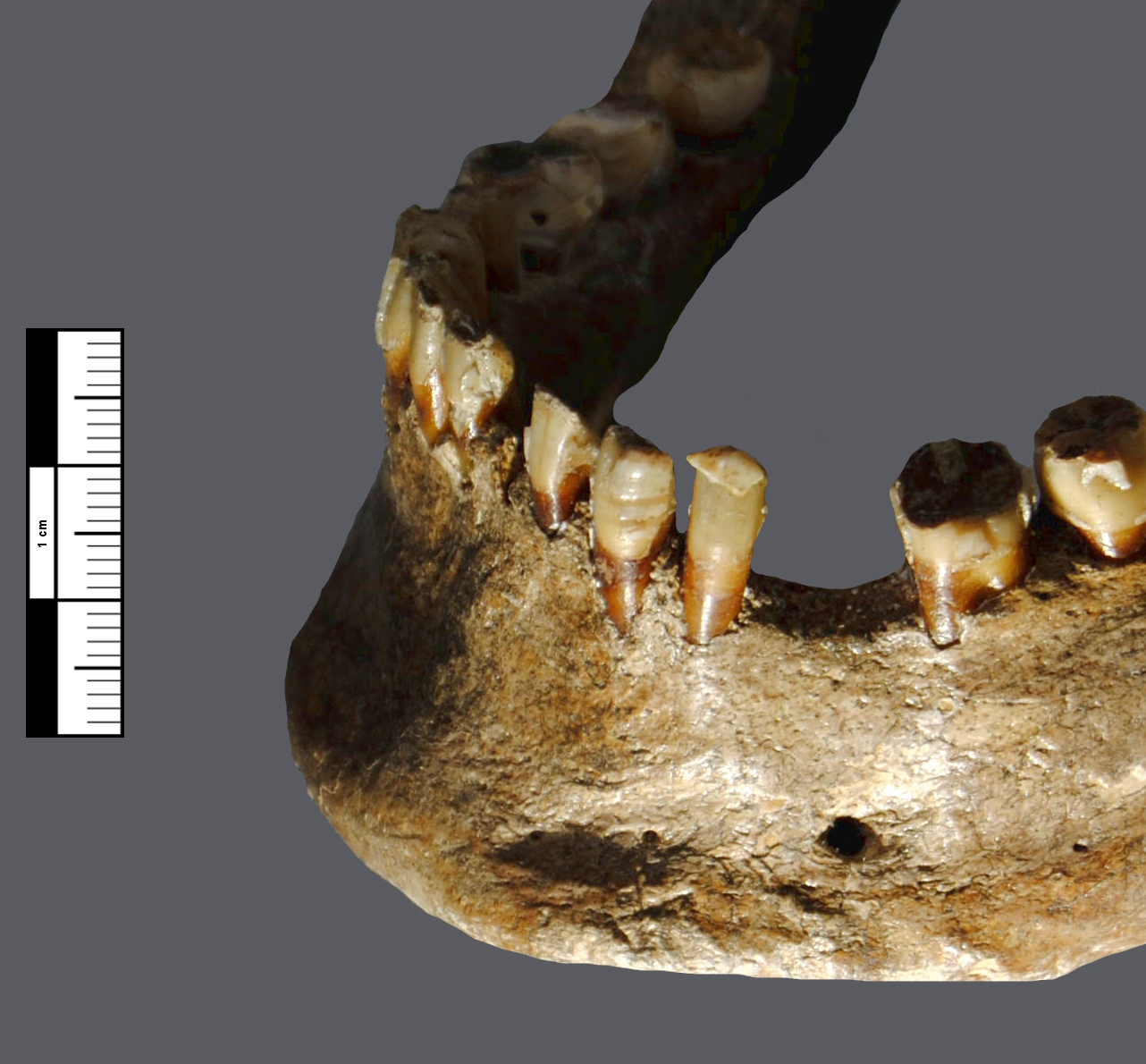

Teeth are a biological window. They contain information that allow researchers to take a closer look into the past and study how people and landscapes interacted. These teeth are from the Viking Age trading settlement of Haithabu on the Baltic Sea, which was the centre of a trading network between Northern and Western Europe from the 8th to the 11th century CE. Anthropologists can use the teeth to identify eating habits and stress situations of malnutrition and diseases in early childhood. Trade and the exchange of goods had a special influence on the nutrition and health of the people in such trading posts. The teeth show at which times there was little food available. The white horizontal lines on the tooth, for example, are indicators of such malnutrition. The import of new trade goods such as new types of grain or livestock in response to periods of drought provided better nutrition, but at the same time changed the existing landscape structure.

Teeth of a mandible from Haithabu | © V. Palmowski

Object details:

Object: Teeth of a mandible

Find location: Haithabu, Schleswig-Holstein

Tractors

Since the 1920s, tractors have become widespread in Germany. They have by and large displaced draft animals from agriculture. The Deutz D30 was one of the most successful models of the 1960s. Like some of its predecessors, it replaced conventional carriages pulled by farm animals as it worked more efficiently. The greater production capacity provided by the use of agricultural machinery led to fewer people being employed in agriculture. They migrated from agricultural areas to urban and industrial regions. Due to the growth of cities, the demand for food increases in urban agglomerations. Conversely, products for agricultural production, such as fertilizers, pesticides and machinery, are developed and produced in urban centres. German examples of this increasingly complex trading network between urban and rural areas are the Ruhr area with Leverkusen and Cologne (Deutz AG) and agricultural regions in Lower Saxony.

Deutz D-30 from 1965 | © T. Rentschler

Object details:

Object: Deutz D-30

Year of construction: 1965

Symbols of Power – (In)visible Representation

Height

King Statues

Fortification

Symbols of Power – (In)visible Representation

The Bronze Age palace in Qaṭna, Syria symbolizes it, as does the imperial crown in the Viennese treasury or a tumulus on Gotland: Power.

Power relations structure modern and pre-modern societies. Power is demonstrated - in objects and buildings, in insignia, or in weapons. These symbols of power have survived as remnants in the ground, as references in historical writings, and in pictorial works. If one wants to understand the diverse nature of power and rulers in past epochs, these objects are valuable sources. That is what this exhibition is about: How did power manifest itself in different times and spaces? What symbols represent it in Antiquity and the Middle Ages in Western Syria, Northern Europe, and the Swabian Jura?

Castle Keep

Hunting

Duck Heads

Scepter

Spearhead

Castle Walls

Symbols of Power on the Swabian Jura

Height

A castle on every mountain – that is how the Swabian Jura is known today. As early as the 16th century, contemporaries valued the noble castles as they denote different territories within a landscape. The painting “Filstalpanorama” was created in 1534/35 due to a dispute between the imperial city of Ulm and the Duchy of Württemberg over rights of way in the valley. In the painting, the castles Staufeneck and Ramsberg on spurs of the Rehgebirge mark different dominions. The location of the castles on the foothill enabled a visual appropriation of the landscape. Widely visible, the castle demonstrated administrative and military power. In castle research, the altitude is also understood as an expression of aristocratic consciousness: The residences demonstrate the distance between the rulers and their subjects.

Filstalpanorama | © Stadtarchiv Ulm: F 3, Ans. 820

Object details:

Object: Höhenburg Staufeneck and Ramsberg on a section of the Filstalpanorama of Martin Schaffner

Location: Stadtarchiv Ulm and Hauptstaatsarchiv Stuttgart

Material: Watercoloured ink drawing on rag paper

Size: 353 cm wide, 44 cm high

Dating to 1535 CE

Castle Walls

In Medieval Times, castle sieges were rare. Instead, castle raids were common. Often, the owners handed the castle over to someone else after being threatened or due to legal processes. However, as special occurrences, castle sieges were often portrayed in art, as this illustration from the Codex Manesse shows.

The 14th century painting demonstrates the significance of a castle in battle: Besides the height of the walls and towers, the strategic position of the castle within the landscape was important for military purposes. Due to the altitude, the castle offered protection and shelter. Further, the castle was used as a strategic center for military actions into its surrounding areas. The castles, thus, were military instruments, and symbols of power.

!["Der Düring" | © Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, Bl. 229v [https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/cpg848/0454] - CC-BY-SA-3.0 © Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, "Der Düring", Bl. 229v [https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/cpg848/0454] - CC-BY-SA-3.0](https://museum-ressourcenkulturen.de/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/3_Burgmauern.jpeg)

"Der Düring" | © Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, Bl. 229v [https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/cpg848/0454] - CC-BY-SA-3.0

Object details:

Object: Visualization of a castle siege within the Codex Manesse

Location: Library of the University of Heidelberg

Material: Topcoat on parchment

Size: 25 cm wide, 35 cm high

Dating to 1305-1340 CE

Spearhead

A rare and special archaeological find has its origins at the Hiltenburg near Bad Ditzenbach in SW-Germany. In late medieval times, the castle was domicile and seat of office to the Counts of Helfenstein. During excavations of the castle keep, the Kreisarchäologie of Göppingen found the 68 cm long iron spearhead in the debris. It dates to November 9th, 1516, the date duke Ulrich von Württemberg destroyed the castle. Originally, the weapon was kept in the tower. The bend spearhead shows that it fell from the tower during the raid of the castle. Prior to its fall into the castle grounds, the weapon was used in battle and for hunting boar and bear. This is also shown in depictions of the Codex Manesse.

Spearhead | © K. Bode/Kreisarchäologie Göppingen

Object details:

Object: Spearhead found at the bergfried (castle keep) of Hiltenburg near Bad Ditzenbach in the county of Göppingen

Location: Landratsamt Göppingen, Kreisarchäologie

Material: Iron, 68 cm long

Dating to the 13th to early 16th century CE

Castle Keep

The typical image of medieval castles in Germany consists of high walls with battlements, a representative residence, and a towering keep. From the castle keep, in the case of the Hiltenburg 30 m high, the surrounding landscape was observed. Further, the tower often acted as treasury of the castle, as valuable objects and documents were stored here. Thus, the castle keep displayed power through its enormous size.

Castle keep | © M. Weidenbacher

Object details:

Object: The two castle keeps (Bergfriede) of the Hiltenburg near Bad Ditzenbach, today used as observation tower and exhibition room.

Location: County of Göppingen

Hunting

The painting in the Codex Manesse shows nobles during their boar hunt. The noble on his horse and his companion are using their swords to slay the animal which was cornered by two dogs. A further huntsman fled the boar and found shelter on a tree.

Hunting was an important component of noble self-confidence and of court life in medieval Germany. The hunt did not only provide meat, but was also used to represent lordly power and proof the own performance abilities. Due to the keeping of horses and dogs, hunting was expensive. Therefore, the distinction between high and low hunt was made. In the high hunt, black and red game were hunted, while the low hunt focused on small animals such as rabbits and foxes.

![Herr Heinrich Hetzbold von Weißensee | © Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, Cod. Pal. germ. 848, Bl. 228r [https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/cpg848/0451] - CC-BY-SA-3.0 © Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, Herr Heinrich Hetzbold von Weißensee, Cod. Pal. germ. 848, Bl. 228r [https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/cpg848/0451] - CC-BY-SA-3.0](https://museum-ressourcenkulturen.de/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/6_Jagd.jpeg)

Herr Heinrich Hetzbold von Weißensee | © Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, Cod. Pal. germ. 848, Bl. 228r [https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/cpg848/0451] - CC-BY-SA-3.0

Object details:

Object: Visualization of hunting scene within the Codex Manesse

Location: Library of the University of Heidelberg

Material: Topcoat on parchment

Size: 25 cm wide, 35 cm high

Dating to 1305-1340 CE

Symbols of Power in Bronze Age Syria

Scepter

Scepters as symbols of kingly power were not only used in Medieval Europe but also in the Ancient Near East. The displayed ivory scepter was found in Western Syria, in Qaṭna, where it was placed into the Royal Tomb between 1500 and 1300 BCE. Originally (around 3000 BCE), a scepter might have been seen as a kind of shepherd’s crook, which was used by the king, the good shepherd, to guide his subjects in godly reign.

The displayed scepter was constructed of three ivory pieces of a hippopotamus’ tusk. The crowning of the scepter seems to imitate the papyrus-like capitals of Egyptian columns, which reflects the many contacts between Egypt and Syria during the second millennium BCE. The indentation at the end of the scepter suggests that originally there might have been a now missing piece present in the scepter. This could have been a gemstone or a precious metal inlay.

Scepter | © P. Frankenstein u. H. Zwietasch, Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart

Object details:

Object: Sceptre

Find location: The Royal Tomb in Qaṭna, Syria

Location today: National Museum of Damaskus

Material: ivory (hippopotamus)

Size: 33 cm long

Dating to c. 1500-1300 BCE (Late Bronze Age)

The scepter was found in the Royal Tomb of Qaṭna, where it lay - together with human remains and vessels of fired clay - in the stone sarcophagus. It was put there as a gift to the deceased member of the local dynasty. The picture shows the position of the light gray sarcophagus in the central tomb of the Royal Tomb. It also contained stone benches with crockery from the ritual funeral banquet and prestigious stone vessels and ornamental objects.

Crypt | © K. Wita, Qaṭna-Projekt, Universität Tübingen

King Statues

The two approximately 85 cm high statues represent the ideal appearance of an Old Syrian king. The hem of the Syrian mantle with rolled borders (the so-called Syrian “Wulstmantel”) surrounding the shoulders and a raised coiffure fixed by a ribbon are visible. A well-groomed beard surrounds the cheeks and chin. This type of depiction was reserved exclusively for kings and gods. The two figures made of basalt, a grey and extremely hard volcanic rock, were originally located to the left and right of the entrance to the royal tomb of Qaṭna. The rulers of stone stood enthroned in front of the tomb until a fire destroyed the palace and buried it under tons of stone and clay brick rubble.

King statues | © K. Wita, Qaṭna-Projekt, Universität Tübingen

Object details:

Object: 2 statues of kings

Find location: Qaṭna Syria at the entrance to the Royal Tomb

Location today: National Museum of Damascus

Material: Basalt

Maße: ca. 85 cm high

Dating to the Middle Bronze Age, ca 1800 BCE (time of production)

From today’s perspective, the fire was a stroke of luck. Through this sudden catastrophe, the arrangement of the statues and the different clay vessels and food scraps placed in front of the statues were preserved. The head of the left statue was discovered in the vicinity of bowls containing food remains. Contemporary sources explain that the food was an offering to the deceased kings. These offerings were for family and religious reasons, but they were also important means of legitimation. By paying homage to his faded predecessors, the incumbent king symbolically placed himself in the long line of an (allegedly) unbroken sequence of venerable ancestors. The high age of the two basalt statues, they had been made some centuries before their last worship around 1340 BC, might have been beneficial to this idea of legitimacy.

Damaged king statue | © K. Wita, Qaṭna-Projekt, Universität Tübingen

Duck Heads

Power can be presented in various forms, although size is not always important. The golden ornament in the shape of two duck heads measures only approximately 7 cm. It still conveys a clear message of political and economic power, as the precious metal gold was used, which was already very expensive at the time. Further, the face of the Egyptian mother goddess Hathor between the duck heads refers to trade contacts with the powerful neighbour Egypt. The impressive details of the piece, such as the naturalistic execution of the duck beaks and feathers bear witness to the precision craftsmanship. Such crafts could not be afforded by anyone, with the exception of the kings of the Late Bronze Age.

Duck heads | © P. Frankenstein u. H. Zwietasch, Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart

Object details:

Object: handle (?) in form of two duck heads, the head of Hathor displayed in between

Find location: Royal Tomb of Qaṭna, Syria

Location today: National Museum of Damascus

Material: Gold

Size: max. 7 cm long

Dating to the Late Bronze Age (1500-1400 BCE)

As there are no parallels to the golden duck heads in Ancient Near Eastern archaeological finds, there are only hypotheses concerning their function. Make-up vessels from Syria and Egypt with duck heads are known, but were usually made of ivory and other materials and only had one duck head, not two. It is, however, plausible that the golden duck heads were part of a bigger object and probably acted as a handle or decoration. Indication for the handle function are the pins at the neck of the duck. These could be placed into indentations within the object to fasten the handle. The eyes of the ducks probably contained gemstones, which are now lost.

Close up of the duck heads | © K. Wita, Qaṭna-Projekt, Universität Tübingen

Symbols of Power in Northern Europe

Fortification

Hedeby – Schleisiedlung, trading center and place of power. The favorable location between North Sea and the Baltic in present-day Schleswig-Holstein made Hedeby one of the wealthiest early medieval settlements of Northern Europe.

Hedeby´s wealth was based on traders, who wanted to avoid the dangerous sail around the Cimbrian Peninsula. Instead, they chose the route via the river Schlei, which led 40 km into the inland and directly to the harbor and trading area.

Control over this important trading route – and thereby Hedeby itself – offered enormous economic power. Another aspect relevant to Hedeby´s significance was its location close to the border between Danish and Franconian Empire. It, thus, was strategically important for military operations.

In the second half of the 10th century, this encouraged Danish king Harald Blauzahn to have the semicircular wall around the settlement erected. The elaborate wall complex is witness to the former meaning of Hedeby as it still structures the landscape today.

Wall | © V. Palmowski

Object details:

Object: Semicircular wall of Hedeby, with a view of the Haddebyer Noor

Location: Hedeby, ca. 6 km South of Schleswig

Material: Earth wall construction

Size: 4-5 m high, 5-10 m wide, 1.3 km long, enclosing an area of 24 ha

Dating: 950-1000 CE